Report on Deutsch, Español & Português Brasileiro

We are writing from the same lockdown conditions here in Athens that we have reported on for months. Despite stringent measures—or perhaps because of the ways that the government has combined these with policies to promote tourism and consumption despite the pandemic—infection rates continue to soar. Hospitals have reached 89 percent ICU capacity accommodating COVID-19 cases.

One ICU bed not used for COVID-19 is occupied by Dimitris Koufontinas, a long-term prisoner from the November 17 group. Over a month ago, we reported that he was on hunger strike, demanding better conditions and to be moved to Korydallos prison in Athens in order to be closer to his family and friends. He has been on hunger strike ever since.

On February 22, Koufontinas asked the doctors to remove the IV providing him hydration in order to escalate his hunger strike to include water. This could make him the first political prisoner to die of a hunger strike in Europe since Bobby Sands (and several other members of the Irish Republican Army) in 1981. On February 23, the prosecutor’s office approved the forced feeding of Dimitris against his will.

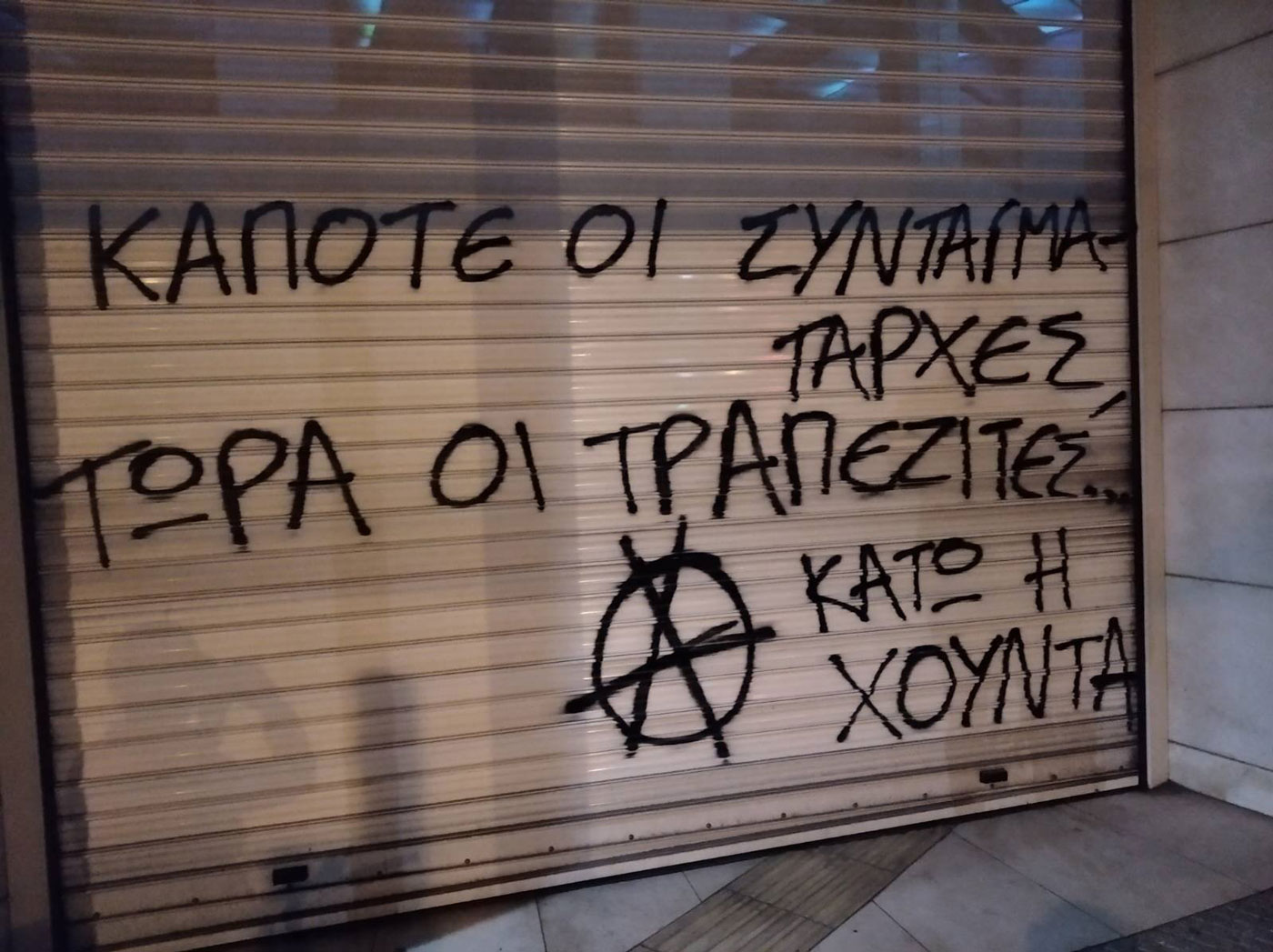

Meanwhile, the New Democracy government continues to use the pandemic to implement far-right policies and target opponents. Behind the genteel manners with which they seek to present themselves as the new political center, the ghost of the military junta that ruled Greece from 1967 to 1974 has come back to haunt the country. Those who rule Greece today are directly descended—some by blood as well as through political lineage—from the Greeks who cooperated with the Nazis to deport the Jews from Thessaloniki and to fight the partisans of Peloponnesus and Pelion. They are the modern-day counterparts of those who collaborated with the US military against the communist guerrillas, using napalm to destroy the forests of Northern Greece.1

New Democracy was the first political party to follow the 1970s Junta. They have been in power many times. The party that preceded them in power this time, Syriza, dramatically betrayed the hopes invested in it. As a consequence, New Democracy won majority control of parliament, placing Greek society entirely at the mercy of a single party. Their campaign hinged on promising their right wing base that they would take revenge against the left, anarchists, revolutionary groups, prisoners, refugees, and other targets of reactionary hatred. When they came to power, they inaugurated a new era of policing and repression involving new technology, anti-terror laws, US-style judicial punishment, so-called “quality of life” policing and investigations, and an unprecedented increase in police state and military funding. This left many in shock.

Remarkably, however, despite facing all of these challenges, the movement is remaining vibrant and visible. People are continuing to struggle against the odds. Facing this post-modern junta, we extend our love to everyone else around the world who is confronting the same neoliberal restructuring and fascist violence.

Dimitris Koufontinas

Dimitris Koufontinas is simply demanding to be moved back to the basement of Korydallos Prison in Athens, where he spent 16 years. He wishes to be closer to his family and legal team. His demand is completely within his legal rights (4760/2020, article 3).

Koufontinas is an accused member of the Revolutionary Organization 17 November (N17), an armed group that employed urban guerrilla tactics between 1975 and 2002. N17 emerged in response to the killings carried out by the Junta, taking its name from the date November 17, 1973, when state forces stormed the gate of the Polytechnic University in the neighborhood of Exarchia with a tank and murdered 24 people, including three teenagers and a five-year-old child. When the group disbanded, Koufontinas voluntarily turned himself in and received a life sentence.

While the history books and the descendants of their political adversaries2 deem them terrorists, N17 had quite a bit of popular support in Greece throughout their existence. For example, many people welcomed the killing of Evangelos Mallios, a policeman who specialized in torture under the junta, following the fall of the military dictatorship.

It is true that Koufontinas is responsible for the deaths of multiple people, including industrialists, domestic and foreign military personnel, fascists, and police. But these deaths took place in the midst of a pitched struggle in which many people were killed on both sides, in which the state employed the vast majority of violent force. Many more people are suffering and dying today as a consequence of the xenophobic policies of the current regime than ever died at the hands of Koufontinas. New Democracy aims to set a precedent by letting him die while refusing to grant his legal rights—a precedent that will surely be extended to others, whether they share his politics or not. For these reasons, while there is much to say about ethics, strategy, and tactics, the most urgent matter is to identify the implications of what the government is doing and mobilize international solidarity.

The Greek government aims to let Koufontinas die rather than honoring the rights that they are legally obliged to grant him. They are doing this, in part, to settle a personal score, as a relative of the Prime Minister was killed by N17. They also intend to send a message that the era of armed resistance in Greece is over, and Koufontinas will be its last face. On February 23, Sofia Nikolaou, the Minister of Prisons—who has used new funds from the state to inflate the salaries of corrections officers rather than providing protective equipment for prisoners, despite COVID-19 running rampant in Greek prisons—stated that Koufontinas is victimizing himself, that the true victims are those he murdered. This indicates that the decision to deny Koufontinas his rights is a calculated symbolic act intended to convey that all political prisoners can expect the same treatment—provided that they are adversaries of the reigning party. One of the first things that the New Democracy government did upon taking office was to release the police officer who killed Alexis Grigoropolous, expressing tacit of approval of his murder of a 15-year-old anarchist.

It is no secret that the New Democracy government is enjoying this moment. Essentially, they are torturing a man who has nothing left to sacrifice but his life, hoping that he will do so. The media likely see his death as a opportunity to shift headlines away from an ally of New Democracy who has been arrested amid charges of pedophilia, and from the failures of the state’s COVID-19 management. Facebook has also taken down posts with hashtags referring to Koufontinas.

Police have repeatedly attacked demonstrations in solidarity with Koufontinas using extreme force. Last week, when protesters occupied the ministry of health in solidarity with Koufontinas, police arrested almost every single participant—the few who managed to escape did so at great risk to themselves. Yesterday, a small crowd carrying a banner was shot with a water cannon at point blank range within minutes simply for gathering and beginning to chant.

But only time will tell what the long-term effects of this moment will be. Despite the curfew, solidarity actions have occurred nightly, including arson attacks on police facilities and paint actions targeting the offices of right-wing journalists.

Behind bars, several political prisoners are engaging in a hunger strike in solidarity. The courage demonstrated by those refusing to let his death go ignored expresses to other participants in social struggles that no matter what the authorities do, no one will be forgotten. For this, we want to humbly recognize and note our respect for everyone who has taken action.

In recent years, Koufontinas has expressed more interest in the anarchist movement as his counterparts on the left distanced themselves from him. Had anarchism been the dominant political perspective of his generation, the N17 group, which practiced illegalism and refused to depend on the state’s theater of parliamentary democracy, might have adopted a different political position. The previously incarcerated political prisoner and Black Liberationist fighter turned anarchist Ojore Lutalo said, “Any movement that fails to support its political internees is a sham movement.” Regardless of the political perspective of Koufontinas, those who maintain their integrity behind bars deserve solidarity.

Koufontinas is 63 years old. There is little hope that he will survive even if the government grants his demand, as he already suffers from long-term effects from previous hunger strikes throughout his imprisonment. He can expect no mercy from this system—and indeed, this extends to all of us. Solidarity is our only hope in such situations. This is why, regardless of how his hunger strike ends, his will to fight against the odds must live on in our own struggles.

We conclude with a poem by Giannis Ritsos, a communist guerrilla who fought against the Nazis, against the US-backed right-wing government in the Greek civil war, and against the Junta of the 1970s, who was repeatedly imprisoned as well. When Koufontinas began his thirst strike, he had this poem published on his official page.

Epilogue – Giannis Ritsos

Please cherish my memory – he said. I walked for a thousand

miles on end without bread and without water, along rocks and through

thorns I walked, to fetch you bread, water, and roses.

I was always faithful to beauty. With a fair mind I gave out

all my fortune. I did not keep my lot. I am poor. With a tiny lily from

the fields I brightened our harshest nights. Please cherish my memory.

And forgive this last sorrow of mine:

I would like – once again – to reap a ripe ear of corn with the

slender sickle moon. To stand at the threshold, to stare away

and to chew with my front teeth the wheat

admiring and blessing this world that I leave behind,

admiring also Him who climbs up the hill in the

golden rain of a sinking sun. There is a purple square patch in his

left sleeve. It is not easy to see. It was this, more than anything else,

that I wanted to show you.

And probably, more than anything else, it would be worth

remembering me for this.

Student Struggles

In Greece, as in Chile, a law designating universities as zones of asylum that police were prohibited from entering came about as a result of military assaults on campuses. The New Democracy regime has abolished the asylum law, allowing police onto campuses without concern for the violence that police have historically inflicted in universities. This decision has provoked massive student demonstrations across the country. In addition, the new policy introduces additional privatization measures targeting educational institutions for the sake of paying back debts to the European Union and “modernizing” Greece according to the visions of the wealthy elite who wish to emulate Northern Europe or what they imagine “America” to be.

The bill arrived in parliament around the same time that the government was forced to abandon an attempt at censoring music lyrics—legislation similar to the Spanish law that justified the arrest of Pablo Hasél, which ignited riots in Barcelona last week. Due to backlash from liberals and street opposition from a strong hip-hop community, the law was not passed—but it foreshadows broader repression policies to come.

All of this is taking place as universities remain closed while the regime attempts to shape a post-pandemic Greece. Street demonstrations and student attempts to occupy schools have been met with ruthless brutality. Students and demonstrators have been beaten and arrested at random. Many end up in underfunded hospitals; in some cases, police have not arrested the victims of their attacks solely out of concern that they might die of their wounds, leaving the arresting officers responsible.

Despite all this violence and the risk of fines and imprisonment for assembly during the lockdown, students and their supporters continue to assemble and show force. Police and media claim these demonstrations are helping to spread the virus, but many participants attempt to socially distance and all wear masks. Such a claim seems hypocritical at best when public transportation remains overcrowded, it is hard for many people to access hand sanitizer or personal protective equipment, and hospital budgets have been repeatedly slashed. Worse, police are starting to use American-style kettling tactics to trap demonstrators together in a small space, dramatically increasing the risk of spreading the virus. Videos of police brutality illustrate the repression that the movement is already experiencing; they also indicate what youth can anticipate on campuses when they reopen.

It is important to emphasize that the university asylum policy was introduced in response to the military junta attacking and murdering so many people at universities in the 1970s. The years of university autonomy represented a beautiful manifestation of youth self-determination in this country. In addition to the fact that our movements have found refuge in the universities for assembly and fundraising, the period of university autonomy was remarkable because it showed how much more peaceful these campuses can be without police presence.

The huge festivals that often took place at universities during the years of asylum, and fact that the universities functioned well without police compared to many campuses in the United States, provide evidence that police are simply unnecessary. In the United States, where there are police forces just for universities, there are nonetheless countless cases of rape, mass shootings, and other tragedies. Bad things can happen in Greece, too, even without police around. But imagine weekly parties on university campuses, involving five thousand or more people, with absolutely no supervision by authorities, without any of the catastrophes we often read about in the United States. Just as the DARE program and the promotion of sexual abstinence in the United States arguably contributed to rebellious drug use and unsafe sexual practices, it could be that those perceived to be keeping the peace are actually instigating what they allegedly are there to protect against.

Many of the young people here have never taken freedom for granted. Regardless of this administration’s desires, it will be years before police are normalized on Greek campuses—if they ever are. We humbly express our respect for the courage that students have demonstrated in the streets, our hope that those who have been brutalized may heal, and our solidarity with those facing significant charges and fines for participating in the unrest. May this struggle continue, and may the police experience the animosity they deserve when they set foot on the campuses when they reopen.

Immigrants

Climate chaos is creating difficult conditions for refugees contained in camps across the country. A surreal once-in-a-lifetime blizzard recently hammered Greece, another blow intensifying the horrific living conditions that so many refugees awaiting asylum in this country face. At the same time, xenophobic policies threaten migrants and even those supporting them. For example, a law created to discourage support for refugees that we mentioned in a report last summer led to the firing of a comrade for a charge of alleged riot in 2010.

This is just one of many laws intended to deter solidarity efforts, terrorize refugees who are already desperate, and intensify the bureaucracy that the new regime is subjecting refugees and migrants to across the country. The refugee crisis is only expected to intensify in the post-pandemic economic crisis.

For More Information

Our past reports from Greece are listed in full here. If you are interested in staying up to date with events in Greece, please follow us on twitter and facebook—provided facebook has not deleted us again. You can easily translate the Greek to your native language. You can also find continuous updates at athens.indymedia.org, as well as @exiledarizona, Abolition media worldwide, Act for Freedom Now, and Enough is Enough. You can donate to an ongoing solidarity fund for persecuted and imprisoned revolutionaries in Greece here.

- The US military experimented with napalm in Greece during the civil war of 1946-49, using it to burn out anti-fascist and communist guerrillas who rejected the US-backed right-wing government that came to power after the Second World War. ↩

- The fact that the current prime minister is related to a person that N17 killed over thirty years ago is indicative of the long-term dynasty continues to hold power at the core of the Greek state. While the junta officially fell almost 50 years ago, its legacies continue. ↩